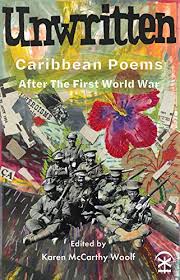

Unwritten – Caribbean Poems After the First World War. Edited by Karen McCarthy Woolf. Rugby: Nine Arches Press, 2018. ISBN: 9781911027294. 122 pages.

Unwrittten – Caribbean Poems After the First World War is a collection of poems which were inspired by the First World War and written by new and established Caribbean poets. The poems were commisioned by 14-18 NOW , the UK’s national programme for the centenary of the First World War, the British Council, and BBC Contains Strong Language. It is a thus a creative and imaginative response to the trauma of the First World War, but from a Caribbean and diasporic perspective.

Karen Mc Carthy Woolf’s introduction replaces the poems and the whole project in their context. The War Poets (Rupert Brooke, Wilfred Owen, Isaac Rosenberg, Siegfried Sassoon) are of course the main point of departure here as they collectively changed the way the Fist World War was perceived and have had such an impact on British people’s view of the war.

As rightly pointed out by the editor, the present collection by no means tries to diminish the importance or the impact of the War Poets, but tries to complement it by providing a new perpective on this tragic event.

The poets explore various aspects of the Caribbean contribution to the First World War, reacting to specific events or to family stories told by their relatives. An important aim of this collection is to make historical archives come to life by focusing on the human element hidden under archival material. A case in point is the story of the Verdala, a ship which carried about a thousand men who were part of the Third Jamaica Contingent. In March 1916, the ship diverted from its course off Halifax and was hit by a blizzard. The West Indian soldiers, who were inadequately clothed and protected, suffered disproportionately. Frostbite was a major problem and there were over a hundred amputations when the Verdala landed in Canada. This tragic incident is addressed by two young poets in this collection, Charnell Lucien, from Trinidad, and Vladimir Lucien, from St Lucia.

In his “Verdala Chronicles”, Vladimir Lucien tells the Verdala story from the point of view of a Caribbean soldier leaving his home island, to be met with a different kind of enemy: not the German troops he expected, but a cold blizzard:

For days, the ship remained out in the bay

watching Halifax, Halifax watching it – us.

For days the snow’s serene bombardment.

For days our ship rocked gently in

the water’s consoling arms, the frigid soft-spoken air

like a useless secretary, bringing no news.(102)

Charnell Lucien’s “Broken Letters” and Tanya Shirley’s “Letter fom France” resort to the letter format, as letters are often what remains in the official archives and help us to understand the trauma experienced by soldiers and their families.

Tanya Shirley’s “December 6, 1918: Taranto, Italy” tells the tale of the Taranto rebellion in 1918, when black soldiers were forced to clean latrines and to take the place of Italian workers. Caribbean myhtology meets history in this poem as Shirley introduces the semi-mythical character of Nanny of the Maroons, a Jamaican eighteenth-century Maroon leader, to convey the idea of Caribbean soldiers’ combativeness and spirit of resistance:

Nanny say I not cleaning any more latrines,

not toiling for no raise of pay.

Nanny say slice a pigeon ope, mix the blood

with gun powder and grave dirt. Smear the face. (112)

Shirley’s poem establishes a link between the First World War and the First and Second Maroon Wars in Jamaica, when the Maroons were often led by obeahmen or obeahwomen, like Nanny, who were feared and respected on account of their magical powers.

Other outstanding poems in this collection seek to recover lost voices or presences in the mother country. For instance, Anthony Joseph’s “Pride” is about George Arthur Roberts, a Caribbean man who fought in both World Wars and lived in Camberwell for many years on the same housing estate as the poet himself. In September 2016, a plaque was unveiled in Roberts’ honour and the estate caretaker, Andrew, seemed to be taking special pride in that event. Past and present are brought together as Andrew, a “rare groover, West London, Jamaican, London soul man” (83), gets to know about Roberts, a “Battalion Bomber” (83) who was “known to throw bombs like coconuts”(83).

Another voice recovered by the creative process is that Norman Washington Manley, one of the founding fathers of the Jamaican nation. Manley’s vivid account of his war experience inspired Anthony Joseph’s “Salt” as well as a beautiful and poetic essay by his grand-daughter, Rachel Manley (“Brothers in Arms”) which focuses on her uncle, Roy Manley, who never came back from the war.

This collection also features beautiful pieces by Kat François, Ishion Hutchinson and Malika Booker, and should have a particular resonance in the light of the recent Windrush scandal which shook Britain in 2018. The Windrush generation recently made the headlines when The Guardian revealed that about 50,000 people faced deportation if they could not prove that they had a legal right to reside and work in the UK. In fact, it was revealed by the media that people of West Indian origin who had been residing in the UK for 40 or 50 years were taken to detention centres to be deported to Jamaica, a country most of them had left at an early age. What happened was that the original Windrush settlers who came in 1948 travelled on “British” passports as countires like Jamaica or Trinidad were British colonies at the time, and the 1948 Nationality Act granted them British citizenship. In 1971 a Commonwealth Immigration Act was passed and restricted access to British citizenship to the people who could prove that one of their grand-parents was born in the UK or had British nationality. The people who came before the passage of this Act had the possibility to formalise their residency status by applying for a British passport, which they had a right to. Many simply forgot to do so, assuming that the British passport they had travelled on in 1948 was still valid. The people who came before 1973 were granted leave to remain by the Home Office and many did not apply for a British passport.

In 2013 when Theresa May was Home Secretary, the government adopted a policy which consisted in making Britain a “hostile environment for illegal immigrants”. The new law required employers, landlords and the NHS to ask for evidence of citizenship or immigration status. Apparently, some Home Office officials applied the law systematically and when Caribbean people were unable to produce documentation that proved that they had been in residence in the UK for decades, they were threatened with deportation. Some of them were unable to produce adequate documentation as the landing cards used by immigrants in 1948 wre destroyed by the Home Office. Proof that these people had been paying taxes in the UK was not accepted. Some Caribbean people lost their jobs, disability benefits or were denied entry back into the UK after visiting relatives in Jamaica. Some of them are still stuck in Jamaica where they are completely lost.

It seems that the Home Office had set removal targets and that officials applied the guidelines quite zealoulsy. The Windrush scandal led to the resignation of Amber Rudd, the Home Secretary, in May 2018 and to her replacement by Sajid Javid. Rudd had originally claimed that there were no removal targets set by the Home Office, but The Guardian published a leaked memo which proved that there were such targets.

In her thoughtful introduction, Karen McCarthy Woolf draws a parallel between the British government’s treatment of Caribbean soldiers during the First World War and the “erroneous and callous deportation” (15) of Caribbean people from the Windrush generation which she refers to as “acts of political vandalism” (15). It is hoped that the present collection will set the record straight concerning Caribbean people’s contribution to British life and culture.