Channer, Colin. Providential. Leeds : Peepal Tree Press, 2015. £8,99. 92 pages. ISBN 9 781845 232481

Colin Channer was born in Jamaica. His father was a policeman and his mother a pharmacist. He is primarily known as a novelist, short-story writer and as one of the organisers of the Calabash festival, which is held every year in May in Black River, Jamaica. His books include Waiting in Vain (One World/Ballantine, 1999) and the novella The Girl with the Golden Shoes (Akashic Books, 2007). Channer has been residing in the USA for a number of years now, has taught Creative Writing at Wellesley College, and has been Writer in Residence at Brandeis University.

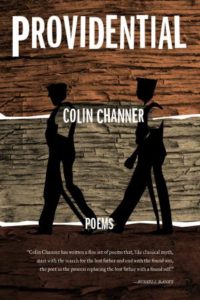

Providential is his first collection of poems and, as can be guessed by looking at the front cover, policemen are at the heart of this collection. Channer’s father was a police constable and many characters who appear in the collection are based on police officers the poet met or heard about.

The collection falls into three sections which follow a roughly chronological progression, starting in Jamaica in 1865, right after the Morant Bay Rebellion, and ending in the USA, with the two long meditative pieces, “Knowing We’ll Be Mostly Wrong” and “Providential”.

Three main themes seem to emerge from these three parts: history, violence, and music.

History looms large in this collection and raises its head in the poem entitled “First Recruits”, which tells the story of the first black police officers who were recruited just after the Morant Bay Rebellion. The Morant Bay Rebellion broke out in 1865 and was a peasants’ revolt due to the dire economic situation at the time and to the limited access to the land for the majority of the population more than thirty years after the abolition of slavery. The poet’s ancestors were among those recruited by the British authorities to form the new Jamaican constabulary, “traitors/falling into place” (Providential 14) as he put it in the last lines of the poem, but also peasants with “big hearts” and ‘sharp eyes”, his people. Channer’s terse style is particularly effective in the description he gives of these humble and decent peasants:

Of those who came,

nine hundred plus were taken.

Sharp-eyes, big hearts,

plenty meat

between the blades.

Feet with arches. (Providential 14)

The ironies of History and of the colonial system also appear in “Civil Service”, a piece about the poet’s grandfather, who wanted a to become a Post Office employee, but became a police constable instead because he was not educated enough and lacked basic literacy skills. The punch line of the poem is quite effective:

They couldn’t trust him

with an envelope. They

issued him a gun. (Providential 28)

The final lines of this poem clinch the argument and point at the ruthlessness of a colonial system which needed loyal and obedient subjects, not educated citizens, to do the jobs that needed to be done.

Violence is another major theme in this first collection, which is not surprising since the poet comes from a family of police officers. Many poems are based on anecdotes or stories which were told to the poet by his father’s friends, who were mostly policemen. The portraits which emerge from these stories are invariably striking and funny at times, with a kind of black humour at play here. The policemen described in these stories often strike or struck badmen’s poses, used violence to do their job, and often behaved in a violent way, like Porter who “spoke justice but believed in fuck-the courts” (Providential 31) and quoted “scripture to the beat of a quick trigger finger” (Providential 31).

A sub-theme in this category of poems is the relentless violence used by policemen and the casual way in which their exploits are recounted, obviously with great relish and gusto, as in the poem entiled “First Kill” which is about a polie constable killing a man for sleeping with his wife. There is a touch of noir in the way the poet relates these events.

Music forms the background to Channer’s first collectuon, and, like Kwame Dawes and Geoffrey Philp, he is one of those poets who work within the parameters of the reggae aesthetics as defined by Dawes in his Natural Mysticism: Towards a New Reggae Aesthetic (Leeds: Peepal Tree Press, 1999). Channer has used the titles of famous reggae songs in the past (for example for his novel Waiting in Vain) and was obviously inspired by this aesthetics. In this collection, reggae is a constant presence, as in the piece entitled “General Echo is Dead”, which is an elegy of sorts for the Jamaican DJ of the same name, but which in fact decries the political violence which led to the death of more than 800 people during the 1980 general election. This poem is dedicated to “Muma Nancy”, in fact Sister Nancy, one of the first women DJs in Jamaica. The poet’s concise style appears in the following lines:

General Echo is dead,

and no one knows.

Big John dropped.

Fluxy silenced.

No more Echo Tone. (Providential 65)

As in “New Recruits”, Channer uses a style which mixes standard English with Jamaican Creole (“Big John dropped”) in a very subtle way.

In “Revolutionary to Rass”, the poet pays tribute to Perry Henzell, who directed The Harder the Come (1972), the film which revelaed Jamaica to the rest of the world with its reggae soundtrack, and in “Occupation”, he draws the reader’s attention to the social divisions which still mar Jamaica today. In “Fugue in Ten Movements”, the late Jamaican singer Joe Higgs’s song “The World is Upside Down” is quoted to pay tribute to one of the founders of that reggae aesthetics which underpins Channer’s collection.

This debut collection is thus quite impressive and is proof that a new, talented poet has arrived on the West Indian literary sene.