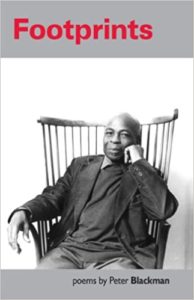

Blackman, Peter. Footprints – Poems by Peter Blackman. Middlesbrough : Smokestack Books, 2013. 106 pages. ISBN : 978 – 0 -9571722-8-9

Peter Blackman (1909-1993) was born in Barbados in 1909 and, after receiving a traditional colonial education at Harrison College, one of the island’s best schools, he studied theology at the University of Durham on a scholarship obtained through the Anglican Church. In 1935 he became a priest and was sent to the Gambia. On arrival, he noticed that black priests ranked lower than white priests and were paid less too. He challenged the authorities over this blatant racism, but finally decided to resign and to go back to Barbados. In 1937 he migrated to Britain where he was to spend the rest of his life. Once in Britain he became very active in West Indian and left-wing political movements like the Negro Welfare Association and the League of Coloured Peoples (LCP). In 1938 he became the editor of The Keys, the journal of the LCP. Blackman was also instrumental in setting up the influentiai Committee on West Indian Affairs to advise politicians on West Indian issues. Around the same time, he joined the British Communist Party. In 1952 his long poem “My Song is For All Men” was published by Lawrence and Wishart both in London and New York. In May 1954 a talk he gave on “Negro Writers” was broadcast by the BBC on its pioneering “Caribbean Voices” programme and in 1948 his article entitled ” Is There a West Indian Literature” appeared in an issue of Life and Letters. Despite these efforts, lack of recognition forced Blackman to work as an engine fitter in a railway depot in Willesden (North London) for most of his life, priding himself on the fact that he was the only mechanic who knew Greek and Latin.

Peter Blackman’s poems were never published in book form during his lifetime, and he remained an obscure figure in the field of Black British and West Indian poetry, never gaining the recognition he deserved. This has now been put to right by the publication of Footprints, which gathers five poems by Blackman, accompanied by a speech he delivered at a meeting organised by Art against Racism and Fascism in 1980.

According to Chris Searle, the editor of the present collection, Blackman’s lack of exposure and recognition could be due to the fact that, after the Second World War, Caribbean writers tried to develop a new literature based on speech rhythms, and the use of Creole. Blackman’s poetry drew its inspiration from the King James Bible, William Blake and Walt Whitman and was thus out of step with the new trends in Caribbean writing. According to Searle, the BBC was not too kind to Blackman and several of his proposed topics for the “Caribbean Voices” programme were rejected.

The collection put together by Chris Searle is an attempt at restoring Peter Blackman to his righful place in the canon of Black British and Caribbean poetry. Searle’s introductory essay places Blackman’s poetry in its appropriate cultural and political context, and gives his readers a sense of who Blackman was, apparently a quiet and unassuming man with a charming personality.

Peter Blackman’s poetry could be said to have its place in the canon of Black British poetry, but it obviously transcended this narrow classification, and was truly eclectic and cosmopolitan. It was also eminently universal and internationalist.

A case could be made for Blackman as an early Black British pioneer, as some of his poems focus on racism and racial discrimination. The poem entitled “London”, which brings to mind William Blake’s eponymous piece, describes the capital in hellish terms :

Grey masks in the dust

Their leprous faces front me darkling,

Full of hate.

Fearful hate,

Spawn of hot-headed rivalry,

Kindred in meannesses.

Millions, so many ;

Bodies sprawling earthwards,

Million bodies soon fragmented into dust,

Bodies mating daily with steel splinters.

God, contemplating these despaired of Hell. (Blackman 45)

In this poem, London is a place where racism is rife since the persona was not able to find accomodation for “a woman and her unborn child,/Since both were black” (Blackman 45).

Blackman also wrote about racial discrimination in the American Deep South in a long narrative poem entitled “Joseph”, about a love affair between a wealthy white woman and her black servant, Joseph. When the local population learnt about the affair, they organised a posse and hanged the black servant.

Blackman’s poetry seems to go beyond the protest mode and includes a universalist and cosmopolitan perspective which appears in his best-known piece, “My Song is For All Men”. This long and wide-ranging poem is an ode to mankind and to man’s thirst for freedom. It includes references to the Turkish poet Nazim Hikmet who had to live in exile because of his political convictions, to Julius Fucik, the Czech poet who was tortured and killed by the Nazis, to Paul Robeson, Toussaint L’Ouverture , Harriet Tubman, Marx, Lenin, and John Brown. Its style is reminiscent of biblical verses and of Walt Whitman’s poetry, with its anaphoras and long lines :

I am Toussaint who taught France there was no limit to liberty

I am Harriet Tubman flouting your torture to assert my faith in man’s freedom

I am Nat Turner whose daring and strength always defied you. (Blackman 60)

In this poem, the persona “rested gently” against himself both the “little blond German child” and the “little black African child” (Blackman 71) in a universal message of peace.

The universal aspect of Blackman’s poetry is also visible in “Stalingrad”, a poem which celebrates the surrender of the Nazi army at Stalingrad in January 1943. This piece reflects the optimism that this historical event gave rise to all over the world, and again resorts to a Whitmanesque style :

Carpenters who had built houses wanted only to build

more

Painters who painted pictures wanted only to

paint more

Men who sang life strong in laughter wanted only to

sing more

Men who planted wheat and cotton wanted only to

plant more (Blackman 34)

On the whole, this collection corrects a major omission and is proof that Peter Blackman was a fine poet. It also confirms Barbados’ important place in the history of Caribbean literature, with novelists like George Lamming and Austin Clarke, and poets like Kamau Brathwaite, Bruce St John and now Peter Blackman. Searle’s detailed and engaging introductory essay provides a wealth of detail about Blackman’s life and work. The only downside to this collection is that it contains only five poems. Hopefully Chris Searle’s research will turn up more material in the future.